Originally

published in

Originally

published in

LEFT OF THE DIAL magazine

issue #1, Nov.2001

From Detroit Inner City Blues to Zen and the Art of the

Studio:

An Interview with the MC5ís Wayne Kramer.

David Ensminger: So youíre working with David Was again?

Wayne Kramer: Yeah, itís that kind of thing. Sometimes I think,

at least on a couple of songs, theyíre too linear, and I need to chop

them up into parts and put them together, like more of a William S. Burroughs

cut-up technique. Sometimes I happen to go in a narrative, and I want

to break that up.

Like a sound collage?

Iíd like it to be. Itís the process which I enjoy so much. Itís problem

solving. You got these amount of elements, so itís like, how do I get

this to go a better way? And I donít know what that is until I roll my

sleeves up and get some mud on the uniform.

With the making of Citizen Wayne, you said you tried to use the studio

as an instrument, while David would ďmerge Wayneís spontaneity with his

digital veg-o-matic.Ē Are you once again using the studio in the same

way?

Yeah, itís a tool. Theyíre all tools. The music itself is a tool.

Language is a tool. Itís all trying to carry a message, something about

wherever I am at the moment. If I can be honest about that, then chances

are someone else is at that moment. And if I do it right, and send a message

to that person that you know, you are not alone, youíre not the only one

that feels that way. Thatís what great art has always done for me. Thatís

what great literature does for me, thatís what great painting does for

me, thatís what great music has done for me. When I hear James Brown or

John Coltrane, I donít feel so alone. Thatís what Iím talking about.

When you capture that moment in your life perfectly, does it then

transcend that moment and become universal?

Well, I donít think there is any perfectly. I just do the best that I

can. Does it become universal? You know, thatís not for me to judge.

But when you hear Sun Ra or John Coltrane, does that happen for you?

Oh yeah. That speaks to me, absolutely.

What exactly is the Mad for the Racket project, which features Stewart

Copeland, Clem Burke, and Brian James?

Well, Mad for the Racket is a real experiment. I used to run into Brian

when I was on tour in Europe, and he kept saying letís do something, letís

make a record. Of course, my standard response is: When? Where?

Whereís

the budget?

Whereís

the budget?

Yeah, letís go. So finally we were together in L.A. and we wrote a record.

We got together for ten days and wrote the record, then it was an easy

matter to get friends to come down to the studio and record it. So the

record is pretty good, I think. Itís real guitar rock. It doesnít stretch

too far. Brian tends to be very true to his vision of punk rock.

Well, heís from the Damned.

Right. He was the lead guitar player in the Damned. I always try and push

something stranger, but we share a lot of common ground, so it was a fun

project to do. So weíll just see what happens. Weíll put it out later

this year and weíll see if people like it. If we can, weíd like to do

some touring.

Would it be fair to compare it to your work with Dodge Main?

Not dissimilar. Of course, itís new material. Itís songs Brian and I wrote.

With Dodge Main we had a fair number of covers. Yeah, youíre right, you

made a good connect the dots there.

You once said about punk, ďMusically, they didnít show me anything.

The Ramones and Blondie were just more of the same.Ē Have Clem Burke and

the rest just come forward enough in their musical style that there is

now fertile ground to work with?

No, I donít think so. Iím not looking to them for that. Cause the real

heavy lifting is in the writing, so I have to write a song, or construct

a song in a way that is more stretched out in order for the musicians

to take it to the next level. If Iím writing a straight up guitar rock

song, the form almost requires that you lay that beat down in a traditional

fashion. And thatís not a bad thing, and when someone does it well, like

Copeland or Burke, then itís a joy.

How much of you on stage is that kid you were at age 9 jumping around

with a broomstick to Chuck Berry tunes? Is it as fresh and invigorating

as listening to music back then?

The thing you are talking about is original joy. Thereís always the elusive

striving to capture that. Of course, you canít. Joy just passes by you,

the best you can do is grab a kiss as it passes. Thatís what we try to

do in a recording session, capture original joy. And thatís what I try

to do in performance, which is keep my mind open and be there right then

in the day Iím in and the moment Iím in, in the song Iím in, and in the

solo I am playing, so that I can grab a kiss from that original joy as

it passes by. Thatís the long answer, and the short answer is yes.

If you could go back in time, you once said youíd like to go to the

NYC jazz scene from around 1950Ė55.

On some level, I identify with that lifestyle. They played these clubs,

they had a camaraderie, there was a kind of club that they were part of

that no one could get in unless you were one of them. I donít know, somehow

I find that a little romantic. Iím intrigued with the idea. Weíre all

so crazy to be musicians in the first place. Thereís a connection amongst

musicians, and I guess I just romanticize that a bit.

But sometimes thereís not enough connection, as in the case of when

you played with Johnny Thunders. He had a different away of approaching

the music than you. So even within the culture of musicians, do you see

things differently?

Absolutely, sure. Weíre not all from a cookie cutter. We run the gamut

of personality types as in any other walk of life. Sure, there are musicians

I prefer not to hang out with (laughs). But amongst my circle of men and

women I consider my friends in music, when Iím with them, and weíre working,

thereís no other place Iíd rather be.

Itís almost a perfect place?

It doesnít get any better. If Iím in a recording studio, and Iíve got

David Was there, and some of the guys from L.A, or some of the players

from Detroit, and weíre doing something that I donít think is too bad,

thereís no place else Iíd rather be in that moment.

Would

that include playing on Simon Stokes new record?

Would

that include playing on Simon Stokes new record?

Absolutely. Iím in the studio, Iím playing my guitar, Iím working with

people I like, and they like me, and weíre getting the chance to do the

kinds of things we like to do. Iím very grateful to be able to do these

kinds of things in this life I have today. Iím grateful to live any kind

of life. Iím happy to be anywhere. By right, I shouldnít be anywhere.

I should be six feet under. So Iím happy to be anywhere.

For people who are not that familiar with jazz, how would you describe

the difference between Sun Ra and John Coltrane?

Iíll put it to you this way, John Gilmore was one of the great tenor saxophone

players that was with Sun Ra for twenty-five years, maybe thirty years,

when he got out of the service. He played in the army band, and he said

that his reading was really strong, and he was trying to decide who he

wanted to go with. He got an offer to play with Coltrane, or with Mingus,

or Monk, and he decided to go with Sun Ra because Sun Raís shit was more

stretched out. In the pantheon of truly cutting edge jazz world, Sun Ra

was head and shoulders above everyone. And had been for years, for years.

I mean Sun Ra ran his band on a whole other level than the rest of us

tried to exist in music. Well, people thought Sun Ra played free music,

and it was all this kind of noise, but Sun Ra was only interested in discipline.

That was all completely controlled, everyone knew exactly what they were

doing. In fact, Sun Ra wasnít interested in freedom, he was interested

in discipline. Not external discipline, but self-discipline.

I suppose you really canít sound free without an element of discipline.

Thatís the thing. Freedom isnít actually free. If you think of freedom

as a coin, on one side it says freedom, and on the other side of the coin

it says self-control, discipline, or something like that.

Your songs often de-romanticize the dope fiend aspect of rockĎní roll,

but also seem to de-romanticize the idea of the lone, mad artist creating

in a vacuum, or by him or herself in the corner. It seems like music for

you happens in a community.

I think it probably does. Iíd agree with that. Itís being part of, as

opposed to separate from. Absolutely, I mean I write these songs so I

could to them myself over and over again. I want people to hear them,

and be part of a lexicon.

Youíve described the old MC5 audience as the greaser, factory rat

contingent back in Detroit. What is your audience now?

Thatís a good question, man. Itís something that I really try and study,

because itís important for me to figure out who the heck is my audience.

And I think they are 35Ė50, I think theyíre older. I think they are music

fans that have grown up with rock íní roll that arenít teenagers, but

still want to rock. They are basically uninterested in whatís happening

in popular music right now because it insults their intelligence. I think

my audience is working people and professional people, probably a lot

of people that have grown kids now, and that are still fans. They donít

go to clubs, but they go to concerts on the weekends. They get a sitter,

and if you let them know enough time in advance, theyíll come out. I also

think my fans are archivists and completists.

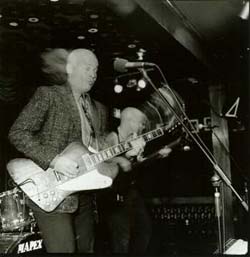

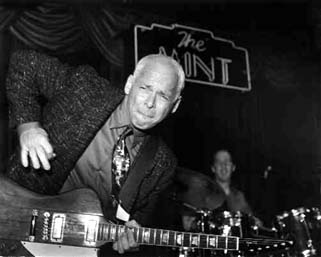

~ Wayne Kramer ~ Photos by William Nettles ~

Whatís your relationship with Epitaph at this point?

I did my contractual commitment to Epitaph, and after 4 albums we mutually

agreed that Wayne would make his own albums. We left on the best possible

terms. Iím still very close with everyone at Epitaph, from Brett to Andy,

to the men and women in the mailroom. Theyíre all still my friends. I

see them all regularly, and I still consider myself an Epitaph artist

at heart because the things I learned at Epitaph about running a record

company ethically and honestly. Itís the same way I am running my own

label now, the same principles I learned by watching how Brett ran the

company, and thatís how I want to run my label. The center never holds,

and however things are today, theyíre not going to be the same four of

five years from now. I knew going in that there was a chance that in four

of five years no one knew what was going to happen. Would Epitaph still

exist? Would they be huge? Would they be bought out? Would they go under?

This is the nature of this business that weíre in. The fact is that they

are doing pretty well. I was there at the time when I was a real anomaly

at Epitaph because Iím actually not a punk. Epitaph fans are basically

about 7Ė13 year old white suburban boys. As much as I like to think that

the young guys would appreciate my work, Iím not writing to them, Iím

not playing for them. I deal with grown up issues, Iím an adult at this

stage in my life. So Iím not talking about what they are interested in.

It was a little bit of a hard fit, because the one thing Epitaph knows

how to do well is sell records to those fans. Itís not really my fan base.

We were just talking about who are the people who buy Wayneís records,

and theyíre not necessarily 7Ė13 year old white suburban boys. Theyíre

not. But I do feel good because we were like the snowplow that opened

the door for Tom Waits and Tricky. And for Epitaph to be able to stretch

out and do other things besides Southern California style punk rock.

Your manager described your Wayne Kramer Presents Beyond Cyberpunk

as a ďthinking manís punk record.Ē Would you describe it the same way?

I suppose. I was just trying to broaden the definition of punk, show that

it wasnít all beats at 160 rpm and flashing guitar, that a mid-tempo ballad

could actually be a punk song, or a twisted up funk track could actually

be punk, or swamp metal could be punk. I think it has much more to do

with a sense of self-determination and self-efficacy that it does a musical

style.

You wrote ďSharkskinís SuitĒ for Charles Bukowski, did a recording

of a Poe poem, and early on were highly influenced by Allen Ginsberg.

How do these writers shape your own art, not just music, but now your

writing?

Itís like how I wanted to learn and play guitar like Chuck Berry. In my

literary efforts itís the same kind of thing. Iíve always admired writers,

and wanted to be a writer. William Burroughs, Ernest Hemingway, and great

crime fiction writers like Elmore Leonard. I love what these guys can

do with character and dialogue. I aspire to that, and in song writing

I have been blessed to have people in my life like Rob Tyner and John

Sinclair and I study Bob Dylan and Tom Waits' lyrics. These guys are gifted

lyricists, even Jackson Browne is a truly gifted lyricist. These are people

I admire and I aspire to their level of competence and their level of

vocabulary in the craft of songwriting. I guess Iím continuing to stretch

that into my prose and the kinds of things I have been writing, like book

reviews and memoirs. We are working on a couple of scripts, so itís just

the continuing work in a creative lifetime. Itís not all that remarkable,

it really is 90 percent perspiration, and 10 percent inspiration. You

have to do the work. I can only go along so long without writing a song

and then I start to feel bad. I go, you know Wayne, itís time to write

a song, you gotta go write a song, other wise youíre going to get in a

crabby mood here. Itís the same with all of it.

We both grew up with a Midwest work ethic, where work matters, it

is important, even a healthy part of our life.

I had no doubt itís my Detroit, blue collar, factory upbringing. I was

basically raised by my mother, and she put such a premium on work. She

worked hard all her life. Itís just what you did. No one gave you nothing.

If you wanted anything in this world, you had to work for it. There were

no entitlements you know. And that was reinforced in the neighborhood,

in the city. Detroit is a city that is all about work. I found, as I got

older, that there was honor in work. There was esteem in work. Even in

the beginning of the MC5 we applied all these principles to how we ran

our band.

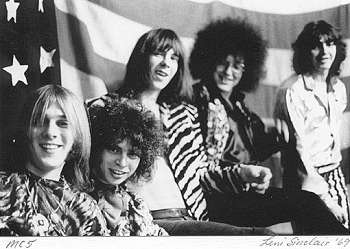

Wayne Kramer, second left ~ photo Leni Sinclair

People donít realize how much work is in rock and roll.

Itís a job when youíre playing five sets a night, six nights a week (laughs).

Forty-five on, fifteen off.

People always talk about the R&B and jazz influences on the MC5, but

your momís boyfriend used to bring home Patsy Cline and Hank Williams

records. Have people missed out on the fact that country music is also

part of your musical roots?

Well, it turns out it is. I kind of denied it for years, because I was

such a staunch rock íní roller, then I became an avant-gardist, but when

I look over the complete path I have been down, those songs are important

to me. Those artists and those Nashville guitar players. Talk about lyric

construction, some of that stuff is fabulous, you know.

ďNo Easy Way OutĒ could easily be a country song.

Youíre right. I havenít thought of it that way, but thatís interesting.

In Fred Goodmanís Mansion on the Hill he discusses the manufactured

blue collar image of Bruce Springsteen. When a guy like Springsteen writes

a song like ďMy HometownĒ then buys a million dollar home, should it matter

to us, or should only the song matter?

Itís not up to me to say what matters for you. I just donít have a problem

with it. Art is very broad, and inclusive, not exclusive. I donít think

that itís okay that songs are exactly true to your life and not okay to

write a complete fabrication, and anything between. Letís keep our feet

on the ground. Thereís real evil in the world. Whether Bruce lives in

a mansion and writes about his poor upbringing is not part of it (laughs).

Who cares, really. If you write a good song, great. If you live in a nice

house, good for you. How many great songs are there that Holland-Dozier-Holland

wrote that didnít have anything to do with anybodyís real life, but that

we all love. That are important to us. Who was Bernadette anyway? Did

she look over her shoulder or not? What was she looking at? What was she

running from?

You mentioned Hemingway earlier. You lived in Key West for awhile.

What was that like?

I had been living in Manhattan for ten years and reached a point where

I felt like I needed a change. I didnít feel like I was any closer to

being happy or being rich, or whatever. I didnít know what I was doing

really. I was kind of like in a rut. I thought, let me go down there.

I met a woman who lived down there and she invited me down. We ended getting

married. It was a nice lifestyle for a couple years. But itís a little

teeny island at the end of the road, and Iím way too ambitious to have

been able to stay there. I want to make movies, I have a lot of records

to make, and a lot of songs to write, and a lot of bands to produce.

Without that time you spent there, do you think you would have been

as productive as you are now?

I think everything we do fits part of a larger plan. If weíre growing

at all, change can be a good thing. I know I was on some kind of a path,

whether I knew it or not. Moving to Key West was part of it.

Will

your lyrics be even more political now that Bush is in office, or turn

towards the personal?

Will

your lyrics be even more political now that Bush is in office, or turn

towards the personal?

I think Iím interested in both. If the last election taught me anything

it was about the illusion of choice. That there is no real choice in the

world, certainly in America, about anything that is important. Like health

care, we donít have any choice in that. Electricity, utilities, those

kinds of things that are importantÖ We donít have any choice in that.

Media, we have no say in any of that. Is it a Republican or Democrat?

Well, whatís the difference? Theyíre both corporate shills. The things

we have choice in are like 31 flavors of ice cream, 50 kinds of bagels.

You get 10 different kinds of sneakers, but that stuff doesnít matter.

Thereís only five record companies. Choices on the important things are

all narrowed down and controlled by gigantic multinational corporations.

Thatís the fact. We have no choice. We have the illusion of choice, like

we all go vote. And believe me I vote, and Iíd vote every day if theyíd

let me. I donít believe itís going to make much difference. I havenít

seen where it makes much difference.

You described the Citizen Wayne songs as auto-mythogizedÖ

Auto-mythological.

Is that still where you are going in your work?

Well, there was a lot of looking back on that record, I was trying to

tell mythological versions of what my experiences have been, but I think

if anything, Iím looking more inward now. So thatís what Iím trying to

do. Iím trying to take a hard look at who I really am. What the hell am

I doing? What am I really all about? What am I really interested in, what

do I really care about? Can I be honest enough? Do I have enough courage

to look really inside and say what I really see? I think thatís what Iím

trying to do.

While imprisoned in Lexington, KY you worked with Red Rodney, who

took you from being a straight rocker to a jazzier player. Is there anybody

influencing you today like Red Rodney did then?

I have a lot of contemporaries. Iím pretty close to guys like Chris Vrenna,

or John X, or David Was remains very close to me creatively. All these

guys are doing things, theyíre showing a high degree of creativity and

courage and pushing music into new spaces. Releasing it from old ideas.

Itís not the same as my relationship with Red, because that was more the

fundamentals of music, the language of music, but I hold these guys pretty

much in the same esteem and I feel like we have a real healthy petri dish

that weíre trying to operate in.

This interview (c) 2001 by David Ensminger

Wayne

Kramer's new release on Muscletone

Records  "Adult

World"

"Adult

World"

Wayne's first solo CD release in over 5 years. It's

a masterpiece. Full lyric sheet. 10 songs that'll slay you.

"...'Adult World' shows Kramer taking another brilliant, fearless leap

into the future--and landing on his feet."

(Jaan Uhelski, RS Online)

Credits: MC5 photo by Leni Sinclair. Photos of Wayne Kramer on stage by William Nettles. Top photo by Stephen Paley.

Acknowledgements

to LEFT OF THE DIAL's publisher David Ensminger and designer Russell

Etchen for their help and kindness and to Margaret Saadi and

Wayne Kramer.

Thanks to Jeff Gold.

Contact LEFT OF THE DIAL's staff at leftofthedialmag@hotmail.com.

Wayne Kramer's official site: http://waynekramer.com